RHS'69

Honouliuli Internment Camp

Monday, August 13, 2018

Read John's other blogs: Building lives one home at a time, A new man one piece at a time, The day the Earth stood still

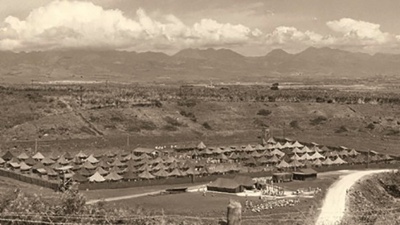

In an isolated location in a deep gulch on the dusty, dry plains near Ewa, a camp was constructed on 160 acres to hold Japanese American internees during World War II.

Some call it Hawaii's secret shame.

Members of the combined class of '69 took a rare tour and John Takara takes us with them.

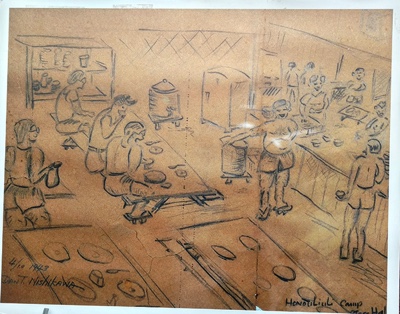

Courtesy: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii

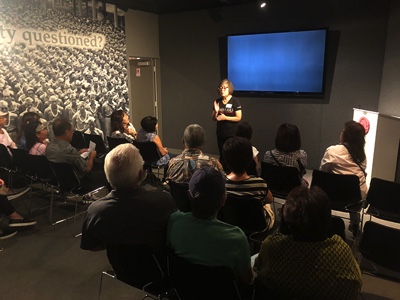

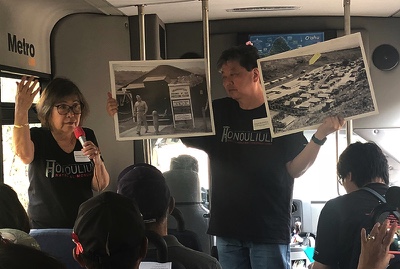

The outing started at the JCC Gift Shop.

From there we watched an introductory video to the site and its historical significance. It was amazing as the history and injustice of the camp unfolded before us.

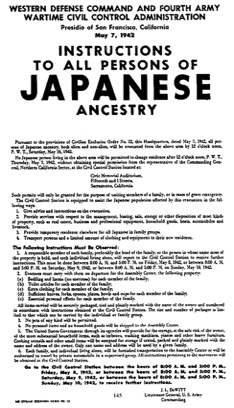

History associates the detainment of Japanese American citizens after the bombing of Pearl Harbor with names like Tule Lake and Manzanar in California. It's not well-known that there were several internment camps established in the western US, including one in the dusty, hot plains of Ewa. It was known as "Hell Valley" by those locked behind its barbed-wire fences.

The majority of Honouliuli's civilian internees were American citizens - predominantly Japanese Americans - who were citizens by birth and suspected of disloyalty. They included community, business, and religious leaders.

Then we boarded a bus to the site.

En route, we were asked to introduce ourselves and to explain why we were on the tour. We learned that the grandfather of Velda Suga Young, a Kalani alumna, was an internee.

As the tour progessed we would learn what a significant role her grandfather had on camp life.

We also learned that Cheryl Osumi, a Roosevelt classmate, also had a grandfather detained there.

Sam Nishimura, a tailor in Haleiwa at the time, had signed a note for a car that was sent to the Japanese Red Cross. It was an innocent act that aroused suspicions about his loyalty.

As we approached the site, we were asked to notice the view, a beautiful panorama of the central Oahu coastline overlooking Pearl Harbor.

That soon ended.

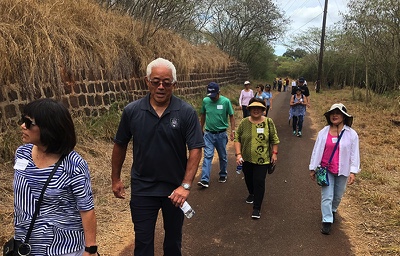

Turning off onto a narrow road, we descended into a narrow gorge overgrown with haole koa bushes. The internees called the campsite, ìJigoku Daniî, hell valley in Japanese.

As we drove deeper into the hot, dusty, isolated regions of the gorge, the view and cooling breezes ended.

The bus stopped, and our attention directed to a pile of boards about 100-feet off the road, barely visible through the thicket. It was the only remnant of the original buildings which once stood on the site. It housed several hundred citizens of Japanese ancestry and about 3000 noncombatant prisoners of war. The authorities targeted leaders in the local Japanese-American community for internment because they were perceived to be a threat to civil order, or even incite revolt in support of a feared Japanese naval invasion.

A short distance away we stopped at a concrete pad alongside the road. It was all that was left of the camp mess hall where they ate food, much of which they raised themselves.

Here the group split, with half continuing on to visit the upper area of the site and the remaining gathered on the concrete pad where the guides described what life was like for the internees.

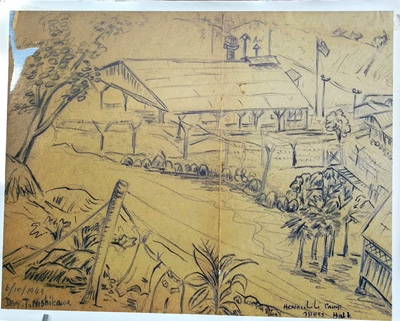

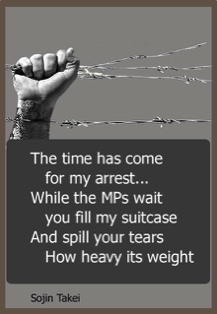

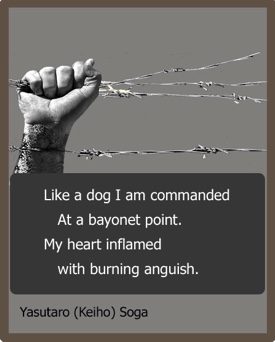

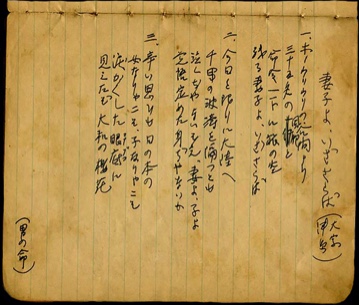

Using stories, photos, internee artwork and poetry, we learned of the difficulties of camp life, the heat, boredom, isolation from family, the anger, the sense of loss and shame.

But we also learned of moments of hope and love, resourcefulness and resilience.

Bored of "haole" food, they got permission to start a garden where they grew and pickled their own vegetables, Japanese style.

They fashioned rings out of tooth brush handles to give as gifts to family.

They saved their rations of grape juice and sugar and had family bring them yeast during visits.

An internee, Mr. Ichiba, formerly the general manager of Fuji Brewery, used the contraband ingredients to secretly brew wine to lighten the burden of daily life. This was Velda's grandfather.

The tour finished with us singing "Honouliuli" (The Unheard Song) written by Alvin Okami while we released handsful of rose petals into the stream behind the former mess hall.

It was an emotional moment and a fitting metaphor of the Honouliuli experience, witnessing fragrant rose petals floating away in a muddy, overgrown stream bed.

It opened in March,1943 and by August there were 160 Japanese Americans and 69 Japanese interned there. The majority of Honouliuli's civilian internees were American citizens, predominantly Japanese Americans, who were citizens by birth suspected of disloyalty.

Designed to hold 3,000 people, it was surrounded by an 8-foot barbed wire fence and 14 guard towers manned by armed military police.

Eventually, the camp held more than 4,000 Okinawans, Italians, German Americans, Koreans, and Taiwanese.

This is the story of the Honouliuli Internment Camp.

Largely ignored in the history of America's WWII internment camps, the significance of Honouliuli has been realized, and the land donated to the US Park Service, which, through the Japanese Cultural Center (JCC), allows limited tours of the site.

On July 11th, twenty-one Roosevelt, Kalani, and McKinley '69 alumni toured the site of the Honouliuli internment camp.

The internment of Japanese Americans in the United States during World War II was the forced relocation and incarceration of between 110,000 and 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry.

Yet, as they remained behind barbed wire, the Army was enlisting nisei soldiers to fight in Africa and Europe. After the war, President Harry Truman told Hawaii's much-decorated, all-nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team, "You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice - and you have won."

After the war, as they tried to resume their former lives, many found that their properties had been seized for nonpayment of taxes or otherwise appropriated. As they started over, they covered their sense of loss and betrayal with the Japanese phrase Shikata ga nai - It can't be helped. It was decades before many could talk openly about the camps.

Photos/video:

Bobby Imoto, Kalani '69

Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii

Various sources